Four Wild Days in December

Revisiting the Clinton Impeachment

The Six-Year Itch

The fall of 1998 was an interesting time to work on the Hill. When a president is in their second term, the midterm elections, known as the “Six-Year Itch,” consistently produce unfavorable outcomes for the party occupying the White House. In modern history, the 1998 elections bucked that trend, with Republicans losing five seats and failing to gain any of the winnable ones.

The messaging of the 1998 election focused on the impending impeachment of Bill Clinton, sparked by a myriad of questionable actions, but fueled by a February 1998 bombshell that he’d had an affair with a 25-year-old intern in the White House. The gambit, masterminded by House Speaker Newt Gingrich, proved to be bad politics, motivating Democrats to get out to the polls. By the end of the week, Newt was out as Speaker, and the battle was on to replace him.

Ironically, an unknown Democratic House member from Lancaster, South Carolina, upset the sitting Republican governor. Little did I know that this would set the stage for Mark Sanford’s 2002 run for governor against Jim Hodges. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

Impeaching a President

By December 1998, I had been working in Sanford’s congressional office for two years. This was between being told I could not be Legislative Director and then being forced into the job. I knew Congress could be chaotic, but this was different. In the space of four days, we saw a sitting president bomb Iraq, the Speaker-designate of the House resign in the middle of a floor speech, and the House of Representatives impeach the President of the United States. Each moment felt like the main event until the next one showed up and knocked it off the front page. You didn’t have time to process what just happened because history was already on to the next scene.

We were caught in the middle of all of it. Not watching it unfold from a distance, but running handoffs and trying to make sense of it all while the country spun itself into a frenzy. If there’s ever been a time when the idea of political theater felt literal, it was those four wild days in December.

Day One: Bombs, Briefings, and a Cancelled Debate

On Wednesday, December 16, we were hours away from beginning the impeachment debate when the president launched Operation Desert Fox. For four days, American and British warplanes pummeled Iraqi targets, intending to degrade Saddam Hussein’s weapons of mass destruction capabilities. On paper, the mission was surgical. In reality, it felt like a political shockwave.

Capitol Hill erupted with suspicion. The timing couldn’t have been more convenient for President Clinton, who was about to become only the second president in American history to face an impeachment vote. The day’s planned proceedings were immediately postponed. Instead of hearing arguments about perjury and obstruction, Members lined up to talk about patriotism and military support. The media ran with the idea that the White House had pulled a page from the “Wag the Dog” playbook.

Sanford wasn’t buying it. When the House took up a resolution expressing support for the troops, he was one of only five members to vote no. Not because he opposed the military. But he questioned the political motives behind the airstrikes and didn’t think the resolution should be used to paper over what was happening. That vote turned heads.

Bob Novak, the conservative host of CNN’s Crossfire, called Sanford to discuss his vote. Sanford laid out the argument that Clinton could have done this at any time, given the intelligence reports we’d had, but he chose now, just as he was being impeached, to send our military to punish Iraq. Novak loved it. The other four no votes had been predictable anti-war votes, but Sanford had an angle.

Day Two: Cable News, Closed Doors, and a Line That Lingered

On December 17, Sanford sat down across from liberal co-host Bill Press and conservative co-host Robert Novak for a Crossfire segment that started with foreign policy but quickly turned personal. The buzz on the Hill wasn’t just about Clinton’s alleged misconduct anymore. It was about Bob Livingston, the man poised to take over as Speaker after Newt Gingrich stepped down.

Livingston had just admitted to a series of extramarital affairs and was attempting to contain the political fallout. The story broke just minutes before Sanford was set to appear on CNN, and he had missed the mandatory Republican Conference meeting where Livingston told Republicans. After that meeting, Republicans lined up to echo their support for Livingston on national television.

I called Sanford to alert him and talk through a response. He was in the makeup chair at the DC studio. “Scott, don’t worry about it, they want to get into impeachment and Iraq. I gotta go.”

“They’re lying, Mark. They’re going to totally talk about this.” But I was talking to myself. He was already gone.

At the top of the show, liberal host Bill Press leaned right into it. When asked if Livingston should still become Speaker, Sanford didn’t hesitate. He said, “He still lied. He lied under a different oath, and that is the oath to his wife. So it has got to be taken very seriously.” He would consider it and discuss it with friends and family, but it was a problem.

Then the phone rang. It was the Speaker’s Office. I refused to answer, but our scheduler did. She handed me the phone, “It’s Alan Martin with Mr. Livingston’s Office.” He was the Chief of Staff and would soon become the top advisor to the Speaker. Or so he thought.

I cheerfully answered the phone, like I hadn’t just watched my boss question out loud on national television whether he could support Livingston as Speaker.

“Mr. Livingston would like to speak to Mr. Sanford,” he said, getting right to it.

“I’m sorry, but Congressman Sanford isn’t here right now…” I got out before he cut me off.

“I’m perfectly aware of where Mr. Sanford is. When can he meet with Mr. Livingston?”

“Well, he’s going to dinner with Congressmen [Steve] Largent and [Lindsey] Graham after his CNN appearance…,” he cut me off again.

“I’m perfectly aware of Mr. Sanford’s dinner plans; he announced them on television. Call me back tonight with a time.”

And the conversation was over.

After the show, I called Sanford. “Hey, Livingston wants to see you.”

“Why?” Typical response from Sanford.

“Something to do with your comments on television. You also have a bunch of media requests.”

“Call Livingston back and tell him we can be there at 8 am. Tell everybody else you can’t reach me.”

“We?”

“Yeah, you’re coming with me.” For once, I did not want to be in the middle of the storm.

“You have a guy for that.” Reminding him that he had a Legislative Director.

“Okay, I gotta go. Get here early.” We weren’t debating it.

I couldn’t sleep that night. It felt like I hadn’t for months. I was losing perspective on time.

Day Three: Words That Carried Weight

Friday, December 18, was even more hectic than the day before. Early the next morning, I met Sanford, and we headed toward the Speaker’s Office in the Capitol. I wasn’t sure how this was going to go. Sanford was reading through news clips and was not very chatty. As we walked into the Capitol toward the Speaker’s Office, I saw Livingston, and he turned toward Sanford. Livingston was easily 6’5” and had one of the shortest fuses on the planet. He had a reputation for getting into near scrums (or real ones) on the House floor.

“Mark, what in the hell were you thinking…” Livingston said as he came at Sanford.

“Bob, I was at a meeting last night. You’ve lost at least 20 votes already, and you’re losing more. This isn’t about me, it’s about you.” Sanford said. Then, just like that, he turned around and walked away.

Suddenly, I’m staring at a red-faced man ready to tear someone’s head off. I turned and ran for Sanford.

“Is he pissed?” Sanford asked, a little too gleefully.

“I thought he was going to kill me.”

“Watch this,” Sanford said as he grabbed AP reporter Alan Fram. He began providing Fram with extensive background information on Livingston, then requested to be identified as “a source familiar with the situation.” He updated Fram throughout the day on the Republican revolt against Livingston.

Day Three: Back to Impeachment

Friday was an incredibly tense day. The Capitol was packed. Security was tight. Everyone knew the vote was coming, but no one knew what the fallout would be.

That afternoon, Sanford met with David Schippers, the Judiciary Committee’s Chief Investigative Counsel. Schippers was a lifelong Democrat who had become one of the most forceful advocates for impeachment. He spoke with conviction about the rule of law and the damage done when lying under oath is treated like a technicality.

Mark came back from that meeting focused. You could see it. He sat in his office and quietly pulled out a legal pad. That night, he went to the floor and gave the most serious speech of his congressional career.

Mr. Speaker, David Schippers, Chief Investigative Counsel for the Committee on the Judiciary, lifelong Democrat and former head of Robert F. Kennedy's Task Force on Organized Crime in Chicago, summed up the one thought that I would like to contribute to this debate. He said before the Committee on the Judiciary, ``The principle that every witness in every case must tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth is the foundation of the American system of justice, which is the envy of every civilized Nation. If lying under oath is tolerated and when exposed is not visited with immediate and substantial adverse consequences, the integrity of this country's entire judicial process is fatally compromised and that process will inevitably collapse.''

I met with Mr. Schippers in the Ford Building this afternoon and became all the more convinced on the need to do something about this principle that he talked about. For those of you in search of a censure, I have come to believe that the constitutional way in which you bring about censure is by sending articles of impeachment from the House to the Senate that go nowhere.

But whether the Senate convicts or not, I think we have to get at what Mr. Schippers was talking about, because, if not, we leave in place one of two very cancerous thoughts. The first would be the President lied, I can too. If people come to believe in a municipal court, a state court, a district court, that when they raise their right hand and promise to tell the whole truth and nothing but the truth, that they can do otherwise, we will have substantial harm to our judicial system.

The other cancerous thought would be I do not know if he lied, but we have two different systems of justice; one for important people like presidents, another one for the rest of us. If we let either of those two thoughts grow, cancerous thoughts grow, we will have substantial harm to our system.

Scott Peck wrote a book several years ago called ``The Road Less Traveled.'' He talked about how often the right road was the hard road, and, therefore, the less traveled road. I think we are on that road tonight, and encourage a vote on impeachment.

He’d chosen a side, very publicly, and that was that the President should be impeached. Not for sleeping with an intern, that wasn’t the question before the House, but for lying under oath, for obstructing justice, and for conduct unbecoming of the President of the United States.

Day Four: The Speaker Who Quit Before the Vote

Saturday, December 19, was supposed to be the day of reckoning. Instead, it started with a curveball.

Early in the last hours of debate, Bob Livingston rose to speak. No one expected what came next. In a calm, deliberate voice, he recounted the divisions that had overtaken the House. He praised the troops. He talked about duty and justice. Then he turned directly to the President.

“You, sir, may resign your post.”

The chamber went silent. But he wasn’t done.

“I can only challenge you in such fashion if I am willing to heed my own words… I will not stand for Speaker of the House on January 6. I shall vacate my seat.”

That was it. The man set to lead the House had just resigned on live television before the impeachment vote had even begun. For the second time in as many months, we didn’t know who would be the next Speaker.

Sanford stood quietly. Two days earlier, he had criticized Livingston on national television. Now, the guy was gone. He didn’t say anything. I guess that said everything.

The bombing in Iraq ceased. Defense Secretary William Cohen and President Clinton declared the operation a success. The ghost of Iraqi weapons of mass destruction would haunt us for years to come.

The Vote and the Echo

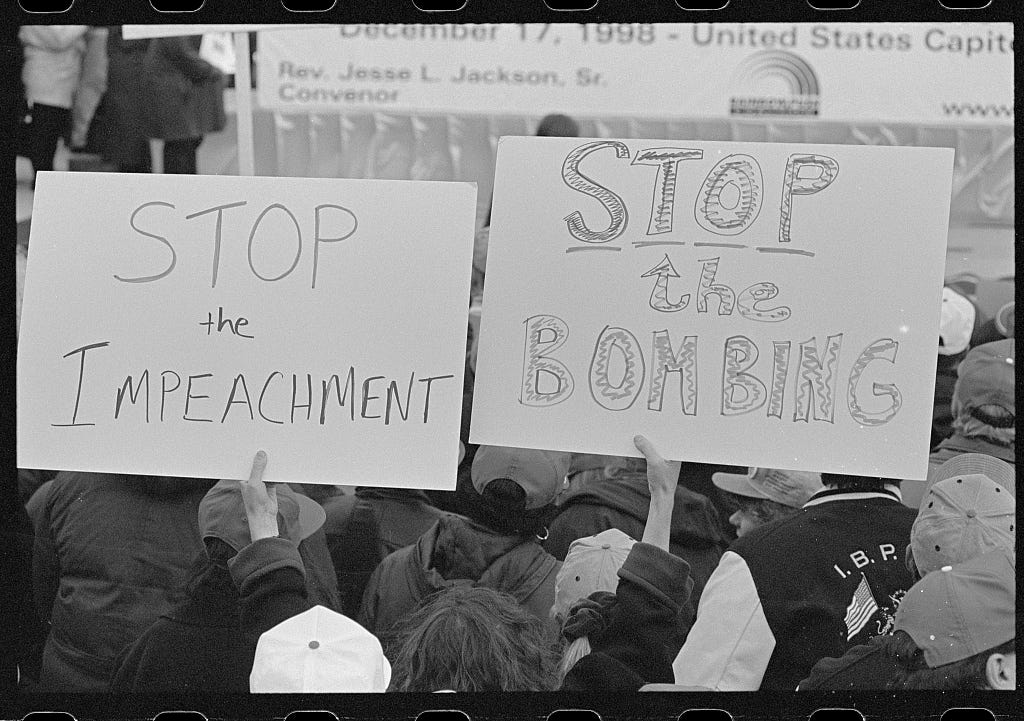

Later that afternoon, the House finally moved forward. Sanford invited the staff to walk over with him to the House floor to witness history. We walked across the street through the mass of people protesting or demanding impeachment. Sanford walked up, cast each vote, and then we walked back to the office.

Two of the four articles passed. Clinton was impeached. It was historic. But it felt different from the day before. The shock of Livingston’s resignation had shifted the tone. It wasn’t a triumph. It wasn’t outrage. It was something else. Something heavier.

The Democrats loaded themselves into buses to head down to the White House. They held a rally with President Clinton and Vice President Gore, defiant to the moment. It was a circus, and there was no way it could have gone any other way. We left the Capitol that night dazed. Not triumphant. Not defeated. Just tired.

The Irony That History Wrote Later

The full-circle moment didn’t arrive until 2009, when Sanford, by then the Governor of South Carolina, disappeared for five days. We’ll revisit the timeline, the tick-tock of events, and try to make sense out of it. But it also resurrected this series of events from 1998 all over again. When we’re at our lowest, the ghosts of our past have a way of resurfacing.

The exact quote about “the oath to his wife” was everywhere. Interpreting the bar he’d set for Livingston as a bar he did not live up to.

People asked if he should resign. Livingston had. Mark didn’t. He finished his term, apologized, and returned to Congress a few years later. Some called it hypocrisy. Some said he showed resilience. Maybe it was both.

Looking back, those four days in December didn’t just define a moment. They defined the gap between the principles we believe in and the people we are. It’s one thing to say what’s right when someone else is under the microscope. It’s something else entirely when the lens swings your way.

What about me?

I made my decision in 2009 when I stayed to hold it together. Professionally, I have always been a firefighter, the person they call when things get bad to fix the problem. In that spot, you focus on solving the problem by any means necessary. I’ve never declared I was virtuous, so decide for yourselves what you think.

Clinton was never removed from office, and he didn’t resign. He got a rally at the White House after using the power of the presidency to obstruct justice for the women he had victimized. I don’t want to get into situational ethics, but it’s inevitable to become a raging cynic in the world of politics if you stay long enough. This is how it typically happens.

If I’ve learned anything, it’s that we need to shorten the careers of every person operating in politics and put massive restrictions on their ability to enrich themselves from the system. Say whatever else you want about me, but I checked out. I didn’t cash out.

But, looking back on 1998, we believed we were doing the hard thing. We just didn’t know how many hard things were still ahead. And none of us saw the Appalachian Trail coming.

Wonderful. Such a titanically flawed man. I'll never forget the intense political attraction I had (from a distance) for a man who seemed to embody a number of fundamental ideological tenets for which I had affection in the early days of the Obama Administration. Sanford was in a class by himself at the time, as he could make a coherent argument and do it in a folksy, effective manner. Your story here about how he reacted to Livingston, and how he did not shy from confronting him reinforces that initial political attraction. What I saw in the Governor's office you oversaw--did much to diminish it. Never meet your heroes, right?