Madison and Hamilton were back for the sequel, and they brought receipts. After ransacking Greek history in Federalist 18, they turned their gaze north to the Holy Roman Empire, otherwise known as the Germanic Confederation. Think of it as Europe’s greatest hits of political dysfunction. Madison treated it like a crime scene. The body was still twitching, but the cause of death was obvious: too many sovereigns and not enough sovereignty.

He called it “a nerveless body.” The Emperor wore the title of ruler but had no real power. Every prince, bishop, and free city guarded its turf, vetoed its neighbors, and begged foreign kings to tip the scales when they could not. It was a government run entirely by HOA boards. Madison’s message was clear. If America had stayed on the path of the Articles of Confederation, it would have ended up just as fractured and helpless.

When Everyone’s a Prince, No One Rules

Federalist 19 opens like a grim diagnosis. The Germanic system, he wrote, “comprises a vast assemblage of republics and principalities, each with its own sovereignty, yet subject in certain cases to the authority of the whole.” That phrase “in certain cases” was the problem. The central authority could propose but never impose. Laws were passed, but only obeyed if convenient. The Diet, their version of Congress, could talk all day, but to act, it needed the consent of every province. Imagine trying to run a country where every law required a unanimous vote in the Senate.

Hamilton and Madison loved their examples. The empire, they said, “has been a continual scene of wars between the states.” Princes would call in France or Sweden for help, and before long, the so-called empire was at war with itself. The supposed union became a geopolitical food fight. “The great engine of their disorders,” Madison wrote, was that the federal head “had not power to enforce the decrees of the Diet, nor even to suppress the insurrections of particular states.” In plain English, no one was in charge.

It was a warning shot. America’s Articles of Confederation created the same kind of ghost government. Congress could vote, but it could not collect taxes, enforce laws, or regulate trade. States bickered over boundaries and tariffs while foreign powers laughed. Madison’s solution was a national government with real authority, one that could compel obedience rather than beg for it.

The Fear Behind the Fix

But here is the rub. The founders’ cure for paralysis was power, and over time, the cure created its own disease. They wanted a government that could act, not just talk. What they built eventually grew into a machine that acts even when no one agrees.

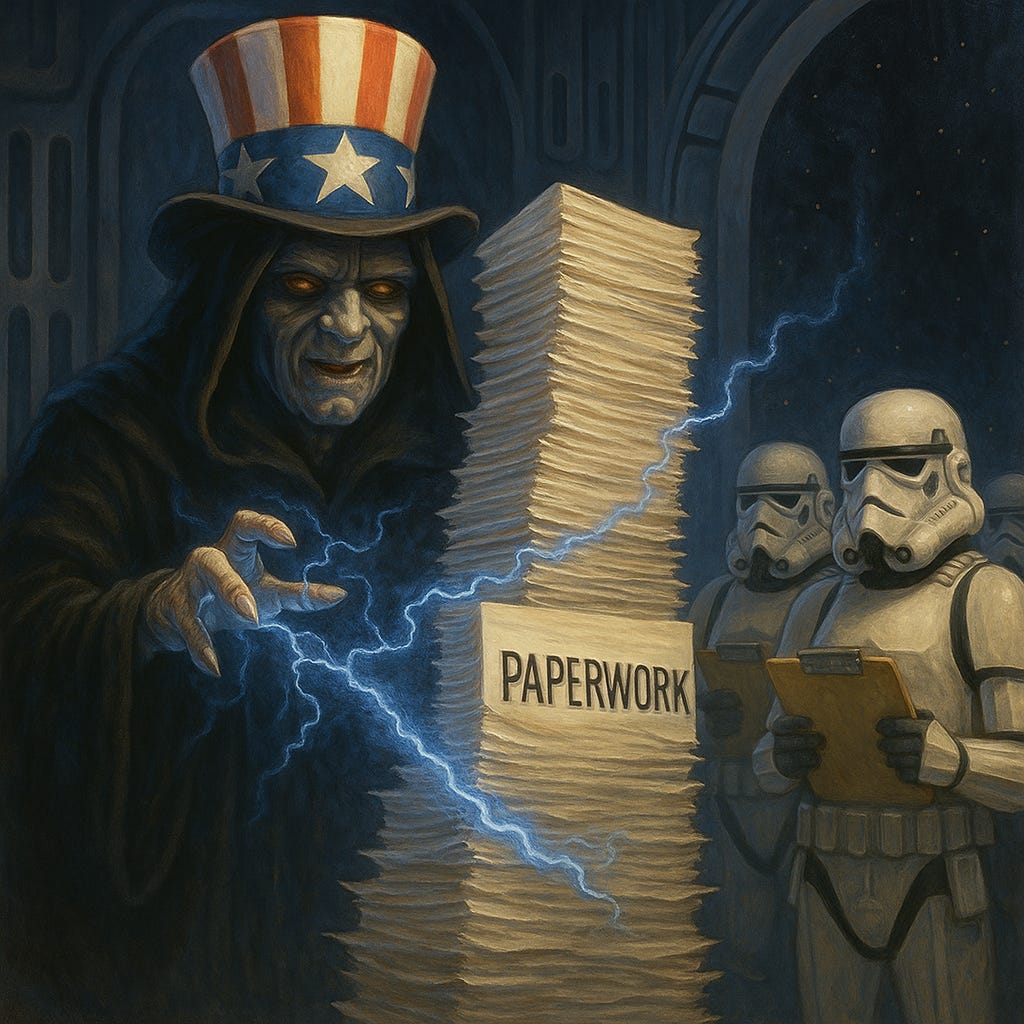

The Anti-Federalists saw it coming. “The government will be so extensive,” wrote Brutus in 1787, “that the people will soon lose sight of it.” He warned that consolidation would create “a power which will annihilate the state governments.” To men like Brutus and the Federal Farmer, the danger was not weakness but drift, a national government that would start as a servant and end as a master.

That prediction has aged like a fine bourbon. Two centuries later, the problem is not too little federal power but too much concentration of it in one branch. What Madison feared in Germany, a confederacy that could not govern, has been replaced by a republic in which the executive governs by default because the legislature cannot.

The Modern Diet: Congress on Pause

When Madison described the Germanic Diet as “a body which deliberates and decides, but whose decrees are without energy,” he might as well have been describing Capitol Hill during a government shutdown. The resemblance is uncanny. Each faction insists on sovereignty, threatens to withhold consent, and blames the other for the standoff. The machinery of government stalls not because power is scarce, but because it is weaponized.

Every few years, Congress re-enacts the same constitutional farce. The government shuts down, workers are furloughed, and federal parks close while politicians hold press conferences about who is to blame. The public tunes out until their tax refunds or travel plans are threatened, and then everyone pretends to be shocked that the richest country on earth cannot keep its own lights on.

If Madison’s Germans were paralyzed by vetoes and divided loyalties, today’s Americans are trapped in a system where veto has become the point. Every negotiation is a hostage situation. Every budget deadline is a cliffhanger. “We must have a government with coercive power,” Madison argued, or we would “soon relapse into the feudal system.” We got that coercive power, just not in the branch he expected.

The Rise of the Imperial Presidency

The vacuum left by legislative gridlock never stays empty. It gets filled by the only branch that can act unilaterally. Presidents now legislate through executive orders, reallocate funds by emergency declaration, and rewrite regulations with the stroke of a pen. What began as a temporary workaround has become standard operating procedure.

Hamilton would probably admire the efficiency. Madison would be horrified by the dependency. When the founders debated how to balance liberty and authority, they assumed Congress would be the strongest branch. They forgot that paralysis itself could create tyranny. As the old saying goes, if you cannot beat the system, the system will beat you, and right now, the executive branch is winning by default.

The irony is rich. Madison and Hamilton wrote Federalist 19 to prove that a confederacy was too weak to survive. They succeeded. But in proving their point, they built a federal system so strong it eventually made the people feel powerless. The confederacy struck back, not through rebellion, but through bureaucratic inertia.

What They Got Right

Madison’s critique of the Germanic Confederation still rings true. Shared sovereignty without a clear center of gravity is chaos. America’s founders were right that unity requires enforcement. They were also right that national defense, trade, and diplomacy cannot be left to the goodwill of individual states. The Articles of Confederation really were a dead end.

The lesson applies far beyond the eighteenth century. Look at the European Union’s current struggles. It can regulate the curvature of cucumbers, but cannot agree on a single foreign policy. Each member state clings to its veto, and global rivals exploit the cracks. The same centrifugal forces Madison described are still at work, only with better branding and a flag with 12 stars.

Even within the United States, you can see the echoes. Federal disaster relief, pandemic policy, and immigration enforcement all turn into contests over who is really in charge. The governors sue Washington, Washington sues the states, and the Supreme Court referees the aftermath. We have not escaped Madison’s confederacy problem. We have just scaled it up to a national level.

What They Missed

Where Madison and Hamilton stumbled was in assuming structure could fix culture. They believed that if you build the right machinery, virtue will follow. But political trust cannot be engineered. The Germanic states failed not only because of weak institutions but also because they lacked a shared identity. Their loyalties ran local, not national.

Madison believed Americans were different. “The people of America,” he wrote in Federalist 14, “are not composed of detached and distant territories.” He assumed a unity of purpose that time has eroded. Two hundred years later, we are less a union of states than a federation of grievance cultures, each convinced the others are ruining the republic.

The deeper problem is not the division of power. It is the division of belonging. We built a government that can act without consensus and then wondered why consensus disappeared. The Constitution gave us stability. It also gave us a mechanism for permanent combat.

The Empire Strikes Back

If Federalist 18 was the origin story, Federalist 19 is the darker middle chapter, the one where the heroes realize their grand design carries unintended consequences. Madison thought he was exorcising the ghost of failed confederacies. In reality, he was summoning a new kind of empire, one that rules not by decree but by drift.

The federal government of 2025 is neither weak nor divided. It is sprawling, procedural, and oddly fragile. Congress can hold hearings, but not pass budgets. States can legislate but cannot coordinate. The President can act, but only until the courts intervene. The citizen, meanwhile, watches from the gallery, unsure who actually governs.

Madison wrote that the Germanic confederation “has ever been kept in a state of imbecility by the intrigues of foreign powers.” Replace “foreign” with “partisan,” and you have the American condition. Our paralysis is self-inflicted. The threat is not invasion but entropy.

The founders feared anarchy. What they got was stagnation. They wanted energy in government. What we have is motion without direction, a perpetual campaign, a government that governs by deadline, and a public so numb it barely notices the alarms anymore.

A Republic Worth Running

The genius of Federalist 19 is that it forces us to confront the trade-off between unity and liberty. Too little unity, and you get Germany under the Emperor. Too much, and you get America under the administrative state. Somewhere between paralysis and overreach lies the republic the founders actually meant to build.

Maybe that is the real sequel, not “The Confederacy Strikes Back,” but “The Republic Fights On.” Madison’s warning still matters, but so does Brutus’s. Power must be strong enough to act and limited enough to listen. Right now, it feels like we have nailed the first part and lost sight of the second.

We keep arguing over who should have the lightsaber: Congress, the President, or the Court, while the ship drifts farther from the planet. The confederacy may be gone, but the dysfunction remains.

The Empire never really fell. It just changed its form.

So well done again! I can’t stop thinking about the 1930 essay from John Maynard Keynes who predicted that developed nations would struggle with the question on how to live agreeably, wisely, and well.

Magnificent. I would take this class.