The Federalists Reloaded | No. 17

Hamilton vs. the Bureaucratic State

Alexander Hamilton was many things: brilliant, brash, relentless. But in Federalist 17, he underestimated the opponent he would face centuries later: the bureaucratic state. Writing to calm fears that the new federal government would consume state authority, Hamilton insisted that Washington would never bother with the details of daily life. The federal government, he wrote, would focus on matters of “general concerns” like defense and commerce. States would remain in charge of local issues, from property and education to law enforcement. The people’s loyalty, Hamilton claimed, would stay with the governments closest to them.

That argument may have sold in 1787. In 2025, it looks like one of Hamilton’s rare blind spots. The modern administrative state is proof that Washington not only concerns itself with local life but thrives on it.

Hamilton’s Promise

Hamilton dismissed the idea that the national government would meddle in “the supervision of agriculture,” or other “objects of a more domestic nature.” Why? Because it would be too much trouble. As he put it:

“It is therefore improbable that there should exist a disposition in the federal councils to usurp the powers with which they are connected; because the attempt to exercise those powers would be as troublesome as it would be nugatory; and the possession of them for that reason would contribute nothing to the dignity, to the importance, or to the splendor of the national government.”

Hamilton also reassured readers that loyalties would naturally bind citizens to their states:

“The people of each State would be apt to feel a stronger bias towards their local governments, than towards the government of the Union.”

In his mind, the greater danger was not federal overreach but state defiance:

“The Union is not likely to be endangered by encroachments of the general government upon the State governments. Rather, the fear ought to be that the State governments, with all the affections of the people, and the greater influence of office-holders, would encroach upon the national authority.”

It was a clever piece of reassurance. But it has not aged well.

Where Hamilton’s Vision Collided with Bureaucracy

The growth of federal bureaucracy rewrote Hamilton’s logic. Instead of focusing only on national concerns, Washington built a machine that feeds on regulation of the local. The list of examples is long, but four stand out.

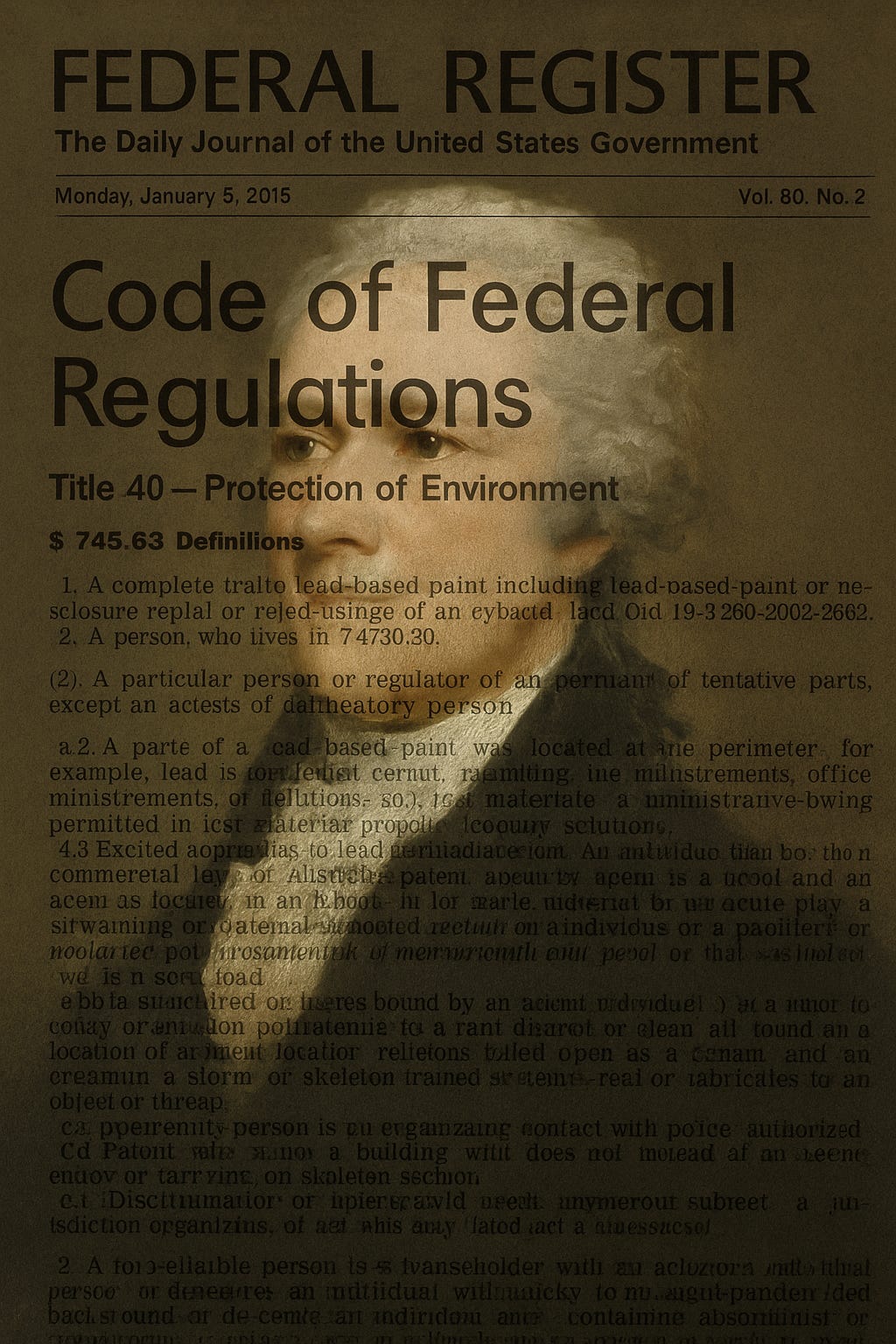

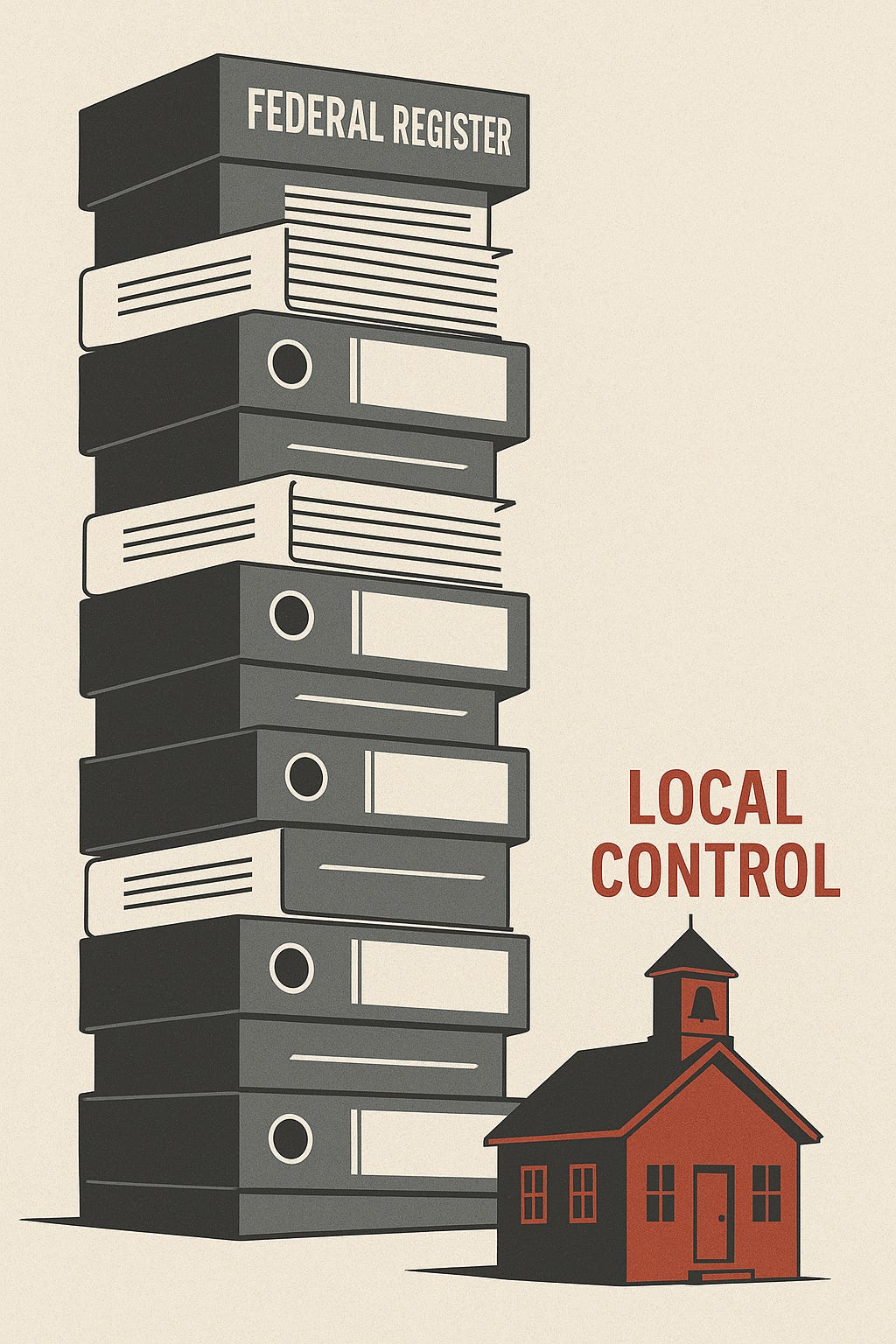

Education. Hamilton assumed schools would remain in the hands of towns and states. Today the Department of Education dictates standards and ties funding to compliance. Student loan forgiveness schemes are launched by federal decree, not local decision. The “little schoolhouse” Hamilton imagined as immune from federal intrusion is now subject to Washington’s purse strings.

Health Care. Public health was once the domain of state and local governments. Now, HHS, CMS, and the CDC set rules that guide hospital policy, insurance design, and even how doctors are reimbursed. During COVID, federal agencies claimed sweeping power to mandate vaccines, regulate masks, and even decide which businesses could stay open.

Agriculture and Land Use. Hamilton mocked the idea that Washington would micromanage farming. Yet farmers today must navigate USDA subsidies, EPA definitions of “waters of the United States,” and school lunch rules written in D.C. The ditch in a farmer’s backyard is not beyond the reach of federal regulation.

Law Enforcement. Criminal law was, in Hamilton’s mind, the most local of all. Today, there are thousands of federal crimes. Agencies like the ATF and DEA often override state policies, from gun regulation to drug enforcement.

This is not Washington avoiding “domestic” matters. It is Washington living off them.

The Anti-Federalist Warning

Hamilton was not without critics. Anti-Federalists warned that once power was granted to the federal government, it would grow. Brutus sounded almost prophetic:

“This government is to possess absolute and uncontrollable power, legislative, executive, and judicial, with respect to every object to which it extends… so far, therefore, as it extends, the government of the States must be annihilated.” (Brutus No. 1)

He later added that the judiciary in particular would erode state sovereignty:

“The judicial power will operate to effect, in the most certain, but yet silent and imperceptible manner, what is evidently the tendency of the constitution: an entire subversion of the legislative, executive and judicial powers of the individual states.” (Brutus No. 6)

And Cato saw the Supremacy Clause as a tool for national consolidation:

“The laws of the Union, which they may enact, are paramount to the constitutions and laws of the several States. The judicial power also will extend to all cases arising under these laws. This will give them an opportunity to construe their own laws, and to decide upon the rights of the citizens in every possible case that may arise in consequence of them.” (Cato No. 5)

Where Hamilton saw restraint, the Anti-Federalists saw inevitability. On this one, they were right.

Why It Happened

Hamilton underestimated two forces. First, bureaucracies seek growth. Agencies are like living organisms. They expand to justify their existence. The incentive is not glory but budget, staff, and jurisdiction. Second, courts stretched constitutional clauses beyond recognition. The Commerce Clause, once meant to regulate trade between states, now covers wheat grown in your backyard (Wickard v. Filburn) or marijuana cultivated under state law (Gonzales v. Raich).

Hamilton’s confidence that the federal government would not bother with “lowly” details collapsed in the face of human ambition and judicial elasticity.

Rounds in the Fight: Modern Case Studies

The battle between Hamilton’s expectations and the bureaucratic state plays out clearly in modern courtrooms and regulatory battles. A few rounds stand out.

Chevron Deference (1984–2024). For forty years, courts gave federal agencies wide latitude to interpret laws under the Chevron doctrine. Agencies could stretch vague statutory language into sweeping new rules. In 2024, the Supreme Court finally scaled this back, forcing agencies to justify their authority with clearer legislative grounding.

West Virginia v. EPA (2022). The Court ruled that the EPA overstepped by trying to restructure the nation’s energy grid without clear congressional authorization. Hamilton assumed Washington would leave local industries alone. Instead, it took the judiciary to remind agencies that they cannot invent sweeping powers out of thin air.

Student Loan Forgiveness (2023). The Supreme Court struck down the Biden administration’s plan to cancel hundreds of billions in student debt. Education, Hamilton thought, was a local matter. Here, Washington not only intruded but tried to do it unilaterally through administrative action.

COVID Mandates (2021–22). OSHA attempted to impose a nationwide vaccine mandate on private employers with more than 100 workers. The Court blocked it, ruling that the agency had exceeded its authority. Nothing illustrates Hamilton’s blind spot more than federal regulators telling small businesses how to handle their employees’ health.

Each of these cases shows what Hamilton missed. The federal government’s temptation is not to avoid the details but to control them. The courts are now playing catch-up, trying to restore the balance he once took for granted.

The Free Market and Limited Government Perspective

Hamilton’s optimism also cost us something important: state competition. When states could control education, business regulation, and health care, they competed to attract citizens and industry. That competition mirrored the free market itself. Federal preemption, however, flattened the field. Instead of fifty experiments in self-government, we often get one-size-fits-all rules from Washington.

And because federal agencies face no market discipline, the normal checks that restrain bad decisions never arrive. A business that makes poor choices loses customers. A bureaucracy that makes poor choices gets a bigger budget. That dynamic is why the administrative state grows while local autonomy shrinks.

The Real Federalist Lesson

Federalist 17 is not just a reassurance to Anti-Federalists. It is also a cautionary tale for us. Hamilton assumed incentives would protect state authority. They did not. What protects liberty is not assumption but hard limits. Separation of powers, judicial vigilance, and public resistance to bureaucratic sprawl are not optional. They are essential.

So when you read Hamilton’s words today, do not take them as gospel. Take them as a reminder of what happens when faith in government’s restraint replaces structural limits on its power.

Closing Thought:

Hamilton believed the federal government would have “no temptation” to interfere with local life. Two centuries later, the bureaucratic state stands as the clearest challenge to his vision. The Founders’ design works only when ambition is checked by structure. On this one, Hamilton lost the fight.

Excellent essay!

Thank you for another thoughtful essay. Makes you wonder whether we will ever get the balance right!