The Federalists Reloaded | No. 13

A More Affordable Union?

The Pitch

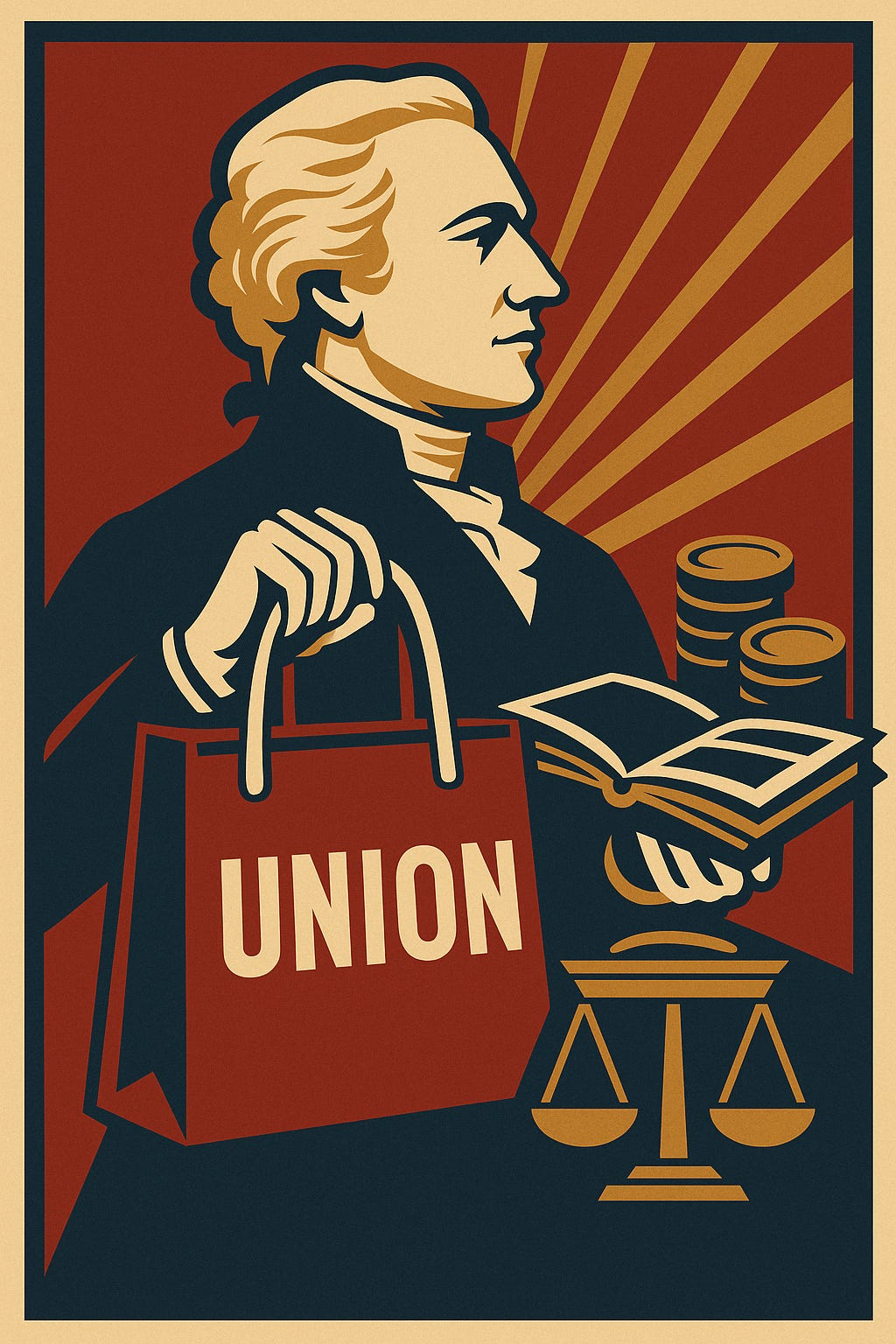

By the fall of 1787, Alexander Hamilton had become the workhorse of the Federalist Papers. James Madison and John Jay were writing, too, but Hamilton was producing essays at a pace that would make even modern bloggers look lazy. And in Federalist No. 13, Hamilton doesn’t aim for soaring rhetoric or philosophical musings. Instead, he goes for the most practical argument he can make: money.

His case was blunt. Keeping the Union together would be cheaper than splitting it apart. If the thirteen states went their separate ways, every confederacy would have to fund its own president, legislature, court system, military, and diplomatic corps. The duplication alone, Hamilton warned, would bleed the people dry. A single Union, on the other hand, meant one government to cover it all.

“As CONNECTED,” he wrote, “they will avail themselves of one national civil list; as DISCONNECTED, they will incur the expense of each having a separate one.” Translation: Why pay thirteen bills when you only need one?

The Bargain on Paper

Hamilton’s pitch was as practical as it gets. A national government would centralize functions, avoid duplication, and manage shared expenses like defense and diplomacy. Even customs revenue could be streamlined through one unified impost system rather than a patchwork of tariffs between squabbling states.

For Hamilton, this wasn’t about abstract ideals. It was about selling the Constitution as a good deal. A Union meant you could get all the services of government at a discount. Call it Hamilton’s version of a bulk-buy warehouse membership: pay once, get more, waste less.

The Skeptics Smell a Trap

The Anti-Federalists weren’t buying it. Brutus, Centinel, and the Federal Farmer all argued that consolidation wouldn’t save money at all. Instead, it would create a government so large, so distant, and so hungry for resources that the costs would explode beyond anything Hamilton imagined.

The Federal Farmer, in particular, warned that the expenses of a consolidated government would be “prodigious.” Once in motion, he wrote, the officials running it would grow “above the control of the people.” Where Hamilton saw savings, the Anti-Federalists saw a machine designed to feed itself endlessly.

It was a classic clash of optimism and pessimism. Hamilton believed the math was too obvious to dispute. The skeptics believed human ambition would always find a way to wreck the ledger.

Hamilton’s Early Victory

In the short term, Hamilton looked like the one who had it right. The early republic did deliver efficiencies. The Tariff Act of 1789 established a uniform impost system, producing steady revenue. His Assumption Plan of 1790 consolidated state debts under the federal government, stabilizing the national credit. The creation of the Revenue Marine gave the government a tool to enforce tariffs and protect commerce across the entire coastline.

These were real achievements, and they mattered. Without them, the Union might not have survived its early years. Hamilton’s logic seemed vindicated. He had promised efficiency, and the young government, at least in those opening decades, delivered.

Fast Forward: The Bill Comes Due

Two centuries later, Hamilton’s neat arithmetic has been buried under a mountain of red ink. The federal debt has passed $37 trillion. Interest payments alone top $1 trillion a year, more than we spend on defense. The Congressional Budget Office projects that debt will climb to 124 percent of GDP in the decades ahead.

This isn’t just a big number problem. It’s the collapse of Hamilton’s argument that the Union would be more economical. Duplication and waste, the very things he said the Union would prevent, are everywhere.

The Pentagon has a budget larger than the next ten militaries combined, yet it cannot pass a full audit. Billions of dollars’ worth of equipment are unaccounted for. In healthcare, Washington runs Medicaid and subsidies while states implement their programs, each with layers of bureaucracy. In education, federal dollars flow through state agencies, which create their bureaucracies, and then into local districts, which add yet another layer. By the time money reaches a classroom, much of it has been eaten alive by administration.

The pandemic turned this into a spectacle. The federal government rushed trillions into the economy, but with systems too weak to monitor fraud, scammers thrived. The Government Accountability Office now estimates more than $200 billion vanished in improper payments.

What Hamilton once sold as a streamlined civil list now looks like the world’s most expensive cable bill, filled with charges no one can explain.

The Real Culprit: Congress

Hamilton’s Union might have worked if someone in Washington had guarded the purse. That job fell to Congress, and Congress failed spectacularly.

Budgets rarely pass on time. Instead, Congress leans on continuing resolutions to keep the lights on. Debt ceiling fights dominate headlines, but they always end with the same result: more spending, more borrowing, more promises to “do better” next time.

Deficits are treated as routine. Trillions roll out the door as though they were rounding errors. And the idea of actual restraint, of saying no, prioritizing, and balancing the books, has become a relic of another age.

Half a century ago, Senator Everett Dirksen quipped, “A billion here, a billion there, and pretty soon you’re talking real money.” It was meant as a joke. Today, the joke is on us. Congress tosses around trillions with the same casual indifference that what Dirksen meant as satire has become standard operating procedure.

The Anti-Federalists Were Right About This

Here’s the uncomfortable truth. Hamilton was right that the Union spared us the chaos of rival state governments. Imagine crossing from Virginia into Maryland and hitting a customs booth, or states fielding their militias against each other. Hamilton’s Union prevented that nightmare.

But the Anti-Federalists were right about the long arc. The “civil list” Hamilton promised would stay lean has become the swollen government they predicted. The national debt proves it. The duplication proves it. And Congress’s refusal to act proves it.

In many ways, Congress is the Anti-Federalists’ Exhibit A. It is the living evidence that consolidation produced not thrift but bloat. Not restraint but excess. Not efficiency but dysfunction.

Where Do We Go From Here?

So what’s the lesson? It’s not that Hamilton was wrong to fight for the Union. Without it, the United States likely wouldn’t exist. But it is a reminder that structure alone doesn’t guarantee efficiency. A single government doesn’t automatically mean a cheaper one.

The real question is whether Congress can ever reclaim its basic function: controlling the purse. Until that happens, the Anti-Federalists will keep looking more prophetic by the year. And Hamilton’s promise that the Union would be the “most economical government” will remain one of the great unfulfilled bargains of American history.

The Last Word

Federalist 13 was Hamilton’s assurance that one government would be cheaper than many. But in practice, the Union has delivered stability at the cost of runaway spending. Congress, unwilling or unable to impose discipline, has turned thrift into excess.

Dirksen’s line about “a billion here, a billion there” no longer gets a laugh. It has become the national operating principle. And for all of Hamilton’s brilliance, the Anti-Federalists win this round.

Congress is their Exhibit A.

Another great history lesson. The ability for Congress to function has been severely compromised by living in the current age of information technology. Thinking of Neil Postman’s book - “Amusing Ourselves to Death, Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business” (1985). Our norms and institutions (e.g. Congress) can’t function if people are unable to think and reason together. Right now, too many people in government treat work as daily TV production to feed media algorithms.