Saying Goodbye to My Father

I was thirteen years old when I went to my first funeral. My father’s youngest sister, Freda, died suddenly from an aneurysm at age 30. She was the cool aunt, rebellious and artistic, the family's black sheep. When we arrived at her viewing, I waited my turn to see her, not willing to look until we walked up to her body. My reaction was what you would expect: I burst into tears, overcome with the loss. My father pulled me into the hallway of the funeral home and leaned in, looked me directly in the eyes, and said, “You can’t cry. They need us. You have to be there for them.” The “they” was my family, my mother, sisters, aunts, and grandmother, widowed and already burying the second of her eight children.

I did my best at that moment, weighed down with a responsibility I never knew I had. That moment, and that sense of duty, are forever burned in my memory. It defines my father and my relationship with him.

Country Folk

My family comes from the Eastern Shore of Maryland, where your family works on the farm or the water. Sophisticated city folks have all sorts of names for us, but we are simply “country folk.” In You Never Even Called Me by My Name, David Allen Coe declared the perfect country and western song had to contain: Mama, trains, trucks, prison, or getting drunk. On the other hand, the rules of coming from country folk are pretty simple:

Always have bail money ready,

Know what members of the family you’re supposed to talk to, and

You always know sorrow.

Before I turned 18, I’d lost three uncles, one aunt, two grandparents, and one step-grandfather. In our house, death was a part of living. When someone in our hometown died, my parents didn’t grieve; they worked. My father hung the black bunting over the doors of the firehouse if they were members of the volunteer fire company, and my mother started working the phones to round up meals for the family of the deceased. As we got older, my sisters and I all got assignments, and that stuck with us all these years later. When my father died, we dutifully convened at our parent's house and started organizing my father’s things and preparing for his funeral. Buried in my father’s files was my mother’s funeral call list, just in case.

The Boy Pater Familias

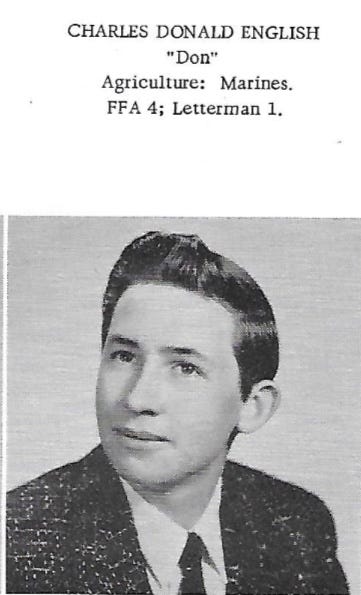

Charles Donald English, or Don to most, was born on September 25, 1941, to Earl Donovan English and Eloise Hazel Hastings, their middle child and only son. In the days before clinical diagnoses, Earl was what folks called a “drunk.” Not the lovable, stumbling drunk like Otis in The Andy Griffith Show, but a self-destructive, harmful to his family type. My grandparents split up officially by 1945. Divorce in the 1940s was for celebrities; everyone else was expected to endure it to the end. My grandmother, and my father, possessed an endurance for pain like none I’ve ever seen. I can only imagine how terrible it was to live with my grandfather that my grandmother would pack up and leave. Fair or not, real or not, my father assumed he was now the man of the family, even after my grandmother remarried and had five more children. That seriousness and sense of obligation followed him for the rest of his life. According to my grandmother, Dad would only see his father once more when he graduated from high school. Even then, he didn’t recognize his father and only afterward found out who it was.

Semper Fidelis

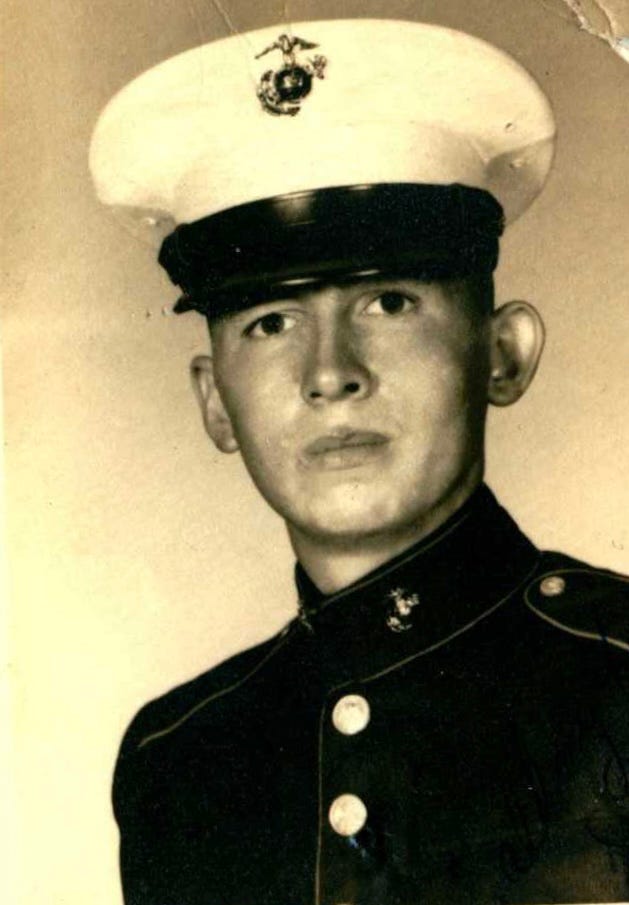

In 1959, Dad graduated from Caroline High School in Denton, Maryland. Though he studied agriculture and belonged to the Future Farmers of America, he wanted to join the United States Marine Corps. According to my grandmother, my father worked at a local general store and spent nights at the local pool hall, hustling and getting hustled. There was a break-in at the store, and money went missing. My father was one of three boys under suspicion for the theft and ultimately given a choice: jail or the military. So in June 1960, my father reported for basic training at Parris Island, South Carolina. In those days, recruits spent sixteen weeks in the swamps of South Carolina’s Lowcountry, and I’m guessing Dad had second thoughts on his choice during July and August. To my knowledge, it was his only serious run-in with the law.

At Parris Island, my father, while on sentry duty, witnessed a drill instructor put a recruit in a garbage can and roll him down four flights of stairs. The recruit suffered a broken arm and collarbone, and an investigation ensued. As the sole witness, my father testified to the events, unsure whether or not it was the end of his young military career. He was told loyalty to the Corps was telling the truth and received a promotion to Private First Class. Dad imposed this same expectation on his children. Corporal punishment was reserved for lying, and it only took a couple of times for me to learn that honesty was the way to go, no matter how brutal the truth was to deliver. So, for all who’ve endured my honesty, you can see how it started.

During his service, he was on a helicopter transport that served as part of the blockade during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. Though he considered reenlistment, Dad had no interest in going to Vietnam, so he returned to Maryland.

The Family Man

In June 1963, my parents were married. Our father then serving in the Marine Corps, and our mother was fresh from high school. The engagement ring and wedding band he gave to my mother were the rings I would give to Kendra almost thirty years later. Together they would have two daughters, Donna and Denise, born fifteen months apart, and a baby boy a few years later. My father wanted to try one more time for a son to carry on the family name, and the third time was the charm. The day my second son was born, my father’s simple observation was, “Well, you always have to outdo me.”

My father wasn’t a warm and fuzzy guy and didn't say warm and fuzzy things. Though he was not religious, he lived by Proverbs 27:17, “As iron sharpens iron, so one person sharpens another.” He set a high standard for his children to work hard in school and do well. When I brought home anything less than a B, I’d be given in-home punishment to reflect on my grades and work ethic. I developed a healthy teenage resentment toward my father. I also graduated in the top ten percent of my class because of him.

In 1965, my dad started as a four-color offset pressman at Western Publishing Company. It was the last job he would ever hold. He worked swing shifts every two weeks: mornings, evenings, and overnight. Every month, employees could buy misprinted or damaged books - a whole bag for just one dollar. Thanks to that job, our house was loaded with books, and we read all the time. Dad had no idea his job would give us a gateway to a better life.

Duty Above All

My parents adopted Trappe as their hometown. Dad joined the Trappe Volunteer Fire Department, serving in virtually every office imaginable in his 50-plus years. When the siren went off, Dad would spring to life, running out the door to get to the firehouse no matter what time of the day or night. The firehouse was our home away from home, and the fire company members were our extended family.

That sense of family was also a sense of duty in times of need. When long-time Treasurer, George Lacey, developed cancer, Dad went to his house almost every day, helping George out of bed and back in at night. Even when George could no longer get out of bed, Dad stayed with him to help with the books. My father took the job as Treasurer after George passed away. It wasn’t glorious, but it kept him connected to George.

Every event in my childhood took place at the firehouse or surrounded by my fire family. My father gave his free time to serve it and the community. I was a junior fireman, cadet, and full member before my career took me away from the social center of the town. Sharing those experiences was the only way I could connect with Dad. Giving up my membership was probably the only time I disappointed my father.

The Politician

When controversy hit our little town, my dad ran for the town council. He offered himself as a reform candidate, backed by a group of concerned citizens trying to change the town government. The year my dad was elected to the town council, the citizens adopted a two-term limit for elected officials. My mother drafted that amendment and worked to get enough signatures to place it on the ballot. When a local reporter asked my father if he supported the term limit initiative, he simply responded, “That was my wife’s idea.” I have no idea whether he supported it, but he honored the will of the voters when he left office eight years later. Despite numerous attempts to repeal the term limits provision, it remains the hallmark of the Trappe government today.

My father was a lifelong Democrat. I shared my story about switching parties and the lecture I endured. The higher my position on Capitol Hill, the more we argued about politics. During Thanksgiving dinner, we had a particularly sharp exchange about the 2000 election, and my mother banned political debates after that. When my father was elected to the Town Council, he pointed out to locally elected Republicans that his son worked for “the Republicans” on Capitol Hill. He said, quite proudly, that he’d raised a son that could think for himself. Give my father credit for being a pragmatic politician.

The Believer

Though Dad wasn’t a religious man, he was a believer. He believed in the best version of every person he met. He let them know when they weren’t living up to that version. If you knew Don English and he didn’t piss you off, you either didn’t know him or you never disappointed him. He also supported people trying to do their best. Typically as quietly as possible so that they got the spotlight. Don’t get me wrong, my father was in the center of many things, but he didn’t need to take anyone else’s thunder to be there.

He was a believer in doing the right thing. Once he decided what that was, he stuck to it stubbornly, even if it wasn’t popular. He fought the unionization of his plant and lost friends over it. When Western went bankrupt, the Cambridge plant remained open. His satisfaction came from knowing that he and his coworkers would keep their jobs.

He was a believer in his community. He gave all his time and energy to our community. He adopted the town and the people, and he lived for them. He hated to leave Trappe and did so only in necessary circumstances. He visited the University of Maryland only once when I needed his truck to move furniture onto campus. As my family's first college student, I wanted to show off the campus. Instead, he closed the tailgate and said, “We have to get back home.”

He was a believer in family. He stuck by my sisters and me through the good times and bad. He was there, no matter what we needed, giving everything he had. For Dad, actions always spoke louder than words, and it was his way of saying, “I love you.” His family grew from three children to five grandchildren and four great-grandchildren by the time he died. He quietly watched over this growing brood, believing the best was waiting for them.

As I dug through my father’s keepsakes, I realized how much I was like him. I didn’t carry his seriousness, I got my mother’s sense of humor, but I have his sense of duty, stubbornness, and belief in doing the right thing. As a kid, I hoped that my father was proud of me. As an adult, I stopped caring whether he was or not. My father was forged from a hard life, and he wanted to make sure he equipped me to face any adversity. Looking back on my life, I realize that toughness served me well in the most extraordinary circumstances.

Life is fleeting, friends, but once someone is gone, that relationship is frozen forever. Cherish the moments you have, and find ways to forgive them and yourself for all the things that could have gone better.

I don’t regret my relationship with my father, as tough and unsentimental as it might seem to people. My regret, as I sit now and sum up my father’s life, is that I never told him I was proud of him.

Goodbye, Dad, and thanks for everything!

Honest and heartfelt Scott. The dynamics between father and son are pivotal to the kind of men we become. Nicely done.

Thanks for resharing this on LinkedIn, Scott.