Burn After Governing

Why the Articles of Confederation Crashed and Burned

Author’s Note: After my most recent post, a reader suggested I do a primer on the Articles of Confederation. It’s a fascinating lead-up to the U.S. Constitution and the arguments outlined in The Federalist Papers. Your feedback is invaluable, and I am having the time of my life. Thank you for reading, and please share this if you enjoy it.

Let’s rewind to post-Revolution America, where 13 ragtag colonies suddenly had to grow up and figure out how to govern a brand-new country. In 1777, they hastily threw together the Articles of Confederation like students cramming for finals. It was finally ratified in 1781—barely. What they created was less a nation and more a polite suggestion to act like one.

The Articles were not only weak but also practically opposed any central power. Having just fought a war against centralized authority, the states had no interest in giving the federal government real power. The result? A system that could barely tie its own shoes, let alone run a functioning republic.

The Skeleton Crew of Governments

Under the Articles, the national government had a Congress but lacked a president, judiciary, or executive branch. Imagine running a company with only a board of directors but no CEO, HR department, or legal team. That was America in the 1780s.

Congress could request funds from the states, but couldn’t compel them to pay. It could negotiate treaties but lacked the power to enforce them. It could declare war, but raising an army was a logistical nightmare. Each state had the authority to coin its own money, levy taxes, and even conduct its foreign policy, functioning like tiny independent republics. There was more coordination at a church potluck than in the Continental Congress.

Even when Congress passed legislation, it was effectively meaningless unless all 13 states agreed. That kind of unanimity in politics is a unicorn, and the resulting gridlock was unavoidable.

Trade Wars, Literally

One of the most glaring issues under the Articles was interstate trade. States taxed each other’s goods as if they were foreign nations. New York slapped duties on Connecticut. Virginia and Maryland squabbled over navigation rights on the Potomac River. There was no consistency, national commerce policy, or smoothly functioning economy.

As James Madison pointed out in Federalist No. 42, this mess of trade regulations made the United States look like “a mere alliance of distinct sovereignties,” incapable of acting in concert.

Congress had no authority to regulate commerce between states or with foreign powers. Each state pursued its economic interests, imposing tariffs and trade restrictions that created a logjam in the arteries of the young economy. One scholar later described the situation as a “commercial civil war.”

Foreign powers took Note. Britain refused to remove troops from the Northwest Territory, and Spain closed off the Mississippi River. Why? Because they accurately judged that the U.S. government was too weak to respond effectively. The Articles left America a fractured shell, and the world wasn’t fooled.

Enter Shays’ Rebellion: The Breaking Point

In 1786, warning sirens blared throughout western Massachusetts. Daniel Shays, a war veteran and struggling farmer, led an armed uprising against state tax collectors and court officials. These weren’t anarchists; they were men who had served their country and were now facing crushing debts and foreclosures.

Shays and his followers closed courthouses, stopped foreclosures, and marched on a federal arsenal. Massachusetts couldn’t suppress the Rebellion without private funds and a volunteer militia. The national government? It lacked both the resources and the legal authority to intervene.

George Washington, retired at Mount Vernon, saw the Rebellion and the federal government’s inability to respond as a flashing red warning. In a letter to Henry Lee, he asked, “What stronger evidence can be given of the want of energy in our government than these disorders?”

Shays’ Rebellion didn’t just rattle local officials; it jolted the entire political class. This wasn’t an isolated uprising; it embodied a Confederation cracking under its own weight.

Warning Shots: The Annapolis Convention

Before the more famous gathering in Philadelphia, there was Annapolis. In 1786, delegates from five states convened in Maryland to address the chaos of interstate commerce. Officially, the meeting focused on trade, but it soon became clear that the system was broken.

Only five states showed up, and there wasn’t even a quorum. However, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison saw an opportunity. They called for a broader convention in Philadelphia the following year. They understood that patchwork fixes wouldn’t cut it. This wasn’t about tweaking a few policies; the entire system needed an overhaul.

Hamilton’s report from Annapolis didn’t sugarcoat the moment: “The crisis is arrived at which the people of America must determine whether they will be respectable and prosperous, or contemptible and miserable.” It was dramatic, but it wasn’t wrong.

The failure of Annapolis to achieve anything was, in itself, the point. The Articles of Confederation didn’t even provide a workable framework for reform. You couldn’t fix the machine because it had no moving parts.

More Signs of Dysfunction

There was no shortage of evidence that the system wasn’t working. Consider Rhode Island, which flooded the market with worthless paper currency. Inflation soared, creditors were stiffed, and economic chaos followed. Madison blasted such laws in Federalist No. 44, calling them “a disgrace to the republic.”

Pennsylvania’s politics descended into factional warfare between populists and conservative elites, leading to legislative gridlock and even the arrest of political rivals. Without a strong federal framework, state-level dysfunction quickly became toxic.

The national government couldn’t enforce the Treaty of Paris, either. States refused to compensate Loyalists as required by the treaty, ignoring federal directives and undercutting America’s credibility on the world stage.

Even disputes between states remained unresolved. Pennsylvania and Connecticut nearly went to war over the Wyoming Valley, while the Confederation Congress could only observe from the sidelines.

As John Jay privately noted, “The inefficiency of Congress appears more and more every day.”

From Collapse to Convention

By 1787, it was clear that the Articles were beyond repair. So, when the states sent delegates to Philadelphia to “revise” them, everyone knew they were really there to replace them.

The Constitutional Convention didn’t just make edits; it started from the ground up. Power was restructured. The new Constitution established a central government with three branches, real taxing authority, a standing army, and supremacy over state laws.

What made this overhaul possible wasn’t just timing; it was the art of persuasion. That persuasion came through a now-famous collection of essays: the Federalist Papers.

Hamilton, Madison, Jay: The Federalist Propaganda Machine

The Federalist Papers were 85 essays published between 1787 and 1788, intended to persuade the public to support the new Constitution. Hamilton, Madison, and Jay not only explained the new government but also dismantled the old one.

In Federalist No. 15, Hamilton didn’t hold back. “We may indeed with propriety be said to have reached almost the last stage of national humiliation.” He described a government that issued requests, not commands, and pleaded with states for cooperation like a teenager asking for gas money.

In Federalist No. 10, Madison focused on the chaos created by factions, something that the Articles failed to control. With each state acting based on its interests, factionalism ran rampant. Madison argued that the new Constitution would expand the republic sufficiently to dilute extremes.

In Federalist No. 51, he added, “If men were angels, no government would be necessary.” The Articles assumed people would play nice. The Constitution anticipated they wouldn’t.

Jay concentrated on foreign policy in Federalist Nos. 3 (TFR No. 3) and 4 (TFR No. 4), cautioning that a divided America would be a weak America. He contended that a centralized government would project strength abroad and safeguard liberty at home.

George Washington’s Shadow

Although Washington didn’t write a single Federalist Paper, his presence loomed large. As president of the Constitutional Convention, his steady hand gave the process legitimacy that few others could provide. He was the ultimate endorsement.

When Washington supported the new Constitution, it quieted many critics. People didn’t know if the system would work, but they trusted the man who had already guided them through one revolution.

One observer put it plainly: “Where Washington leads, men follow.”

Privately, he called the Articles “a half-starved limping government.” The phrase stuck because it rang true.

Lessons From the Failure

The Articles of Confederation taught the Founders a tough but necessary lesson: a government that cannot govern is merely a group of people writing strongly worded letters.

The Articles failed because they tried to protect liberty by removing authority. However, chaos isn’t freedom; it’s another form of tyranny.

The Constitution served as the response, balancing federal and state power, adding enforcement mechanisms, and equipping the national government with the tools to act decisively.

The Federalist Papers weren’t just a PR campaign but a philosophical post-mortem on a failed experiment. They didn’t merely ask Americans to embrace something new; they showed why the old way had to go.

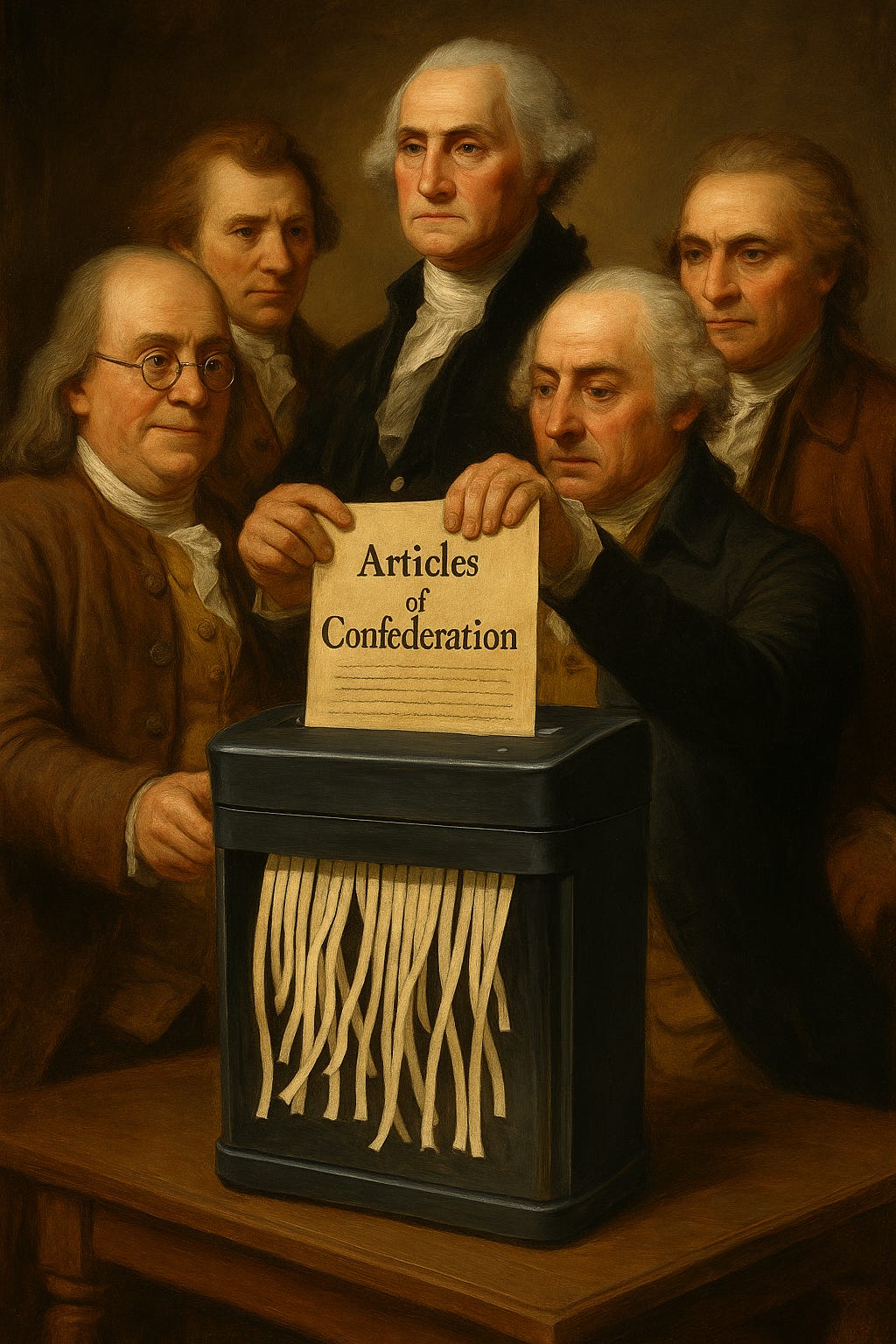

Final Thought: Shred Your First Draft

The Articles of Confederation were America’s first try at self-government—and like most first drafts, they weren’t great. However, they served their purpose. They made clear what didn’t work, prompting the country to think bigger, act bolder, and write smarter.

So yes, the Articles were necessary. But they weren’t sustainable.

To paraphrase Hamilton: if your government can’t make laws, enforce them, or raise an army, it’s not a government. It’s a ghost.

So they tossed the blueprint and started over. That’s when the real union began.

"The Articles failed because they tried to protect liberty by removing authority. However, chaos isn’t freedom; it’s another form of tyranny. The Constitution served as the response, balancing federal and state power, adding enforcement mechanisms, and equipping the national government with the tools to act decisively." This captures the required balance so well! Too much decentralization within a network of cooperation leads to chaos and anarchy; too much centralization within a network of cooperation leads to dystopia in the form of authoritarianism and totalitarianism. Human seem to need to learn that lesson over and over, particularly as changes in information technology impacts human nature and our institutions.