Built by Conflict

What Keith Richards taught me about working for Mark Sanford

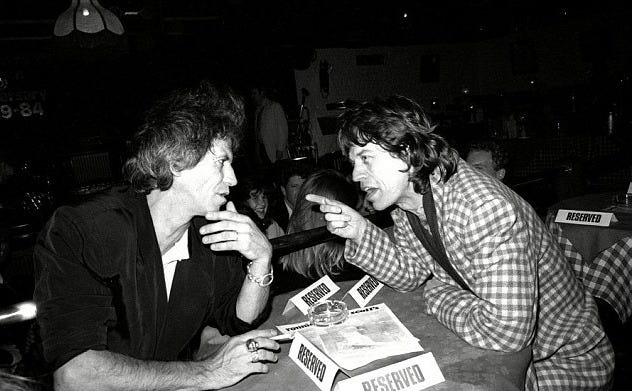

Keith Richards once summed up his working relationship with Mick Jagger like this:

The only things Mick and I disagree about are the band, the music, and what we do.

That quote says more than most biographies ever could. The Jagger-Richards dynamic, combustible and codependent, was never about harmony. It was about tension. And that tension didn’t just shape The Rolling Stones. It drove them. Jagger was the image guy, carefully curating every press shot and PR move. Richards was the chaos agent, walking into the studio with a cigarette, a riff, and a gut instinct. One planned, the other detonated. Together, they created something legendary.

I never imagined a political career would mirror a rock-and-roll relationship, but that’s exactly how it felt working for Mark Sanford. He was the frontman. I was the wildcard. And somehow, for all the dysfunction, it worked. Until it didn’t.

Brand vs. Movement

From the outside, it might have looked like a traditional staff-to-principal relationship. But inside the walls of our office, both on the Hill and later in South Carolina, it was its own unpredictable performance. Sanford was obsessed with the Brand. It wasn’t just a message. It was a lifestyle. He needed every press release, every floor speech, every interview to reinforce the image he had constructed. Clean, fiscal, principled. Above the political fray, even when standing right in the middle of it.

I understood the Brand and had been enlisted to protect it, but what I wanted was a Movement. That meant elevating issues, framing debates, and, occasionally, kicking the hornet’s nest when it served a larger purpose. Chaos wasn’t a threat to me. It was a tactic. If Sanford was the strategic frontman worried about lighting and sound check, I was the guy in the back of the van figuring out which club we could crash and still get paid.

That dynamic didn’t click immediately. It took time. It took arguments. It took trust, built slowly and uneasily, often through conflict and adversity. And at the center of it all was the growing tension between how each of us approached leadership and control.

The HR Black Hole

If there’s one area where Sanford’s management flaws were impossible to ignore, it was HR. The higher you climbed in the operation, the more obvious it became. What looked like organized chaos from the outside was often just chaos on the inside. There were processes, sort of. There were plans, sometimes. But when it came to personnel decisions, Sanford had two speeds: dismissive and impulsive.

I learned that lesson the hard way in the fall of 1998. I had been on staff for two years and had grown into a reliable legislative aide. When our Legislative Director announced he was leaving for a think tank, I thought I had a shot at the job. I mentioned it to our Chief of Staff, who said she’d float it to Sanford.

A few days later, I got the call. Sanford wanted to meet. I assumed this would be my chance to make the case, to talk through what I’d learned, what I saw coming in the final session, and how I planned to keep our office on mission. I didn’t even get to sit down.

As I stepped into his office, he looked up from his desk and said, “April told me you want to be the LD. You’re a smart guy, but you’re not organized. You don’t look beyond the 30-day range. We need a plan for the last session, and I don’t think you’re up to it. So, sorry, but it ain’t happening.”

That was it. No conversation. No feedback. Just a one-sentence verdict. I'd been dismissed before the case was even heard.

I walked out of his office pissed. There was no new job, no transition plan, and a third child on the way. I called the Chief in Charleston and gave her an ultimatum. “You’ve got one week,” I said. “I want a $7,000 raise and a promotion to Senior Legislative Assistant, or I’m gone.”

I reminded her every day. On day seven, she called to say it was done. Mini-crisis averted, for now.

The Office That Killed Two Careers

Over the next four months, the revolving door began to turn. We went through two Legislative Directors. Nice guys, both of them. And both were entirely unprepared for Mark Sanford.

We had just moved into a new office space, shifting from 1228 Longworth to 1233. The new space was 500 square feet larger, which may not seem like much, but for us, it was a palace. It was also closer to the House floor, which aligned perfectly with his chronic habit of waiting until the very last second to leave for a vote. Every foot counted.

The first new LD—let’s call him Bill—decided that in the new space, he needed a private office. On the Hill, a private office means walls but no ceiling. You get noise, echoes, and the illusion of privacy. I never saw the appeal. He never got to see it either.

A couple of weeks after Bill arrived, we went out for dinner at Tortilla Coast, which had become something of an institution for Team Sanford. The atmosphere was tense. Sanford spent the evening peppering Bill with questions about the year ahead. Every time I tried to jump in, Sanford cut me off with “I asked Bill.”

Bill got fired that night.

Our second LD—let’s call him Sam—walked into a trap he didn’t set. The office Bill had planned was set to be built. Sam, maybe hoping to assert some authority or just trying to make the best of things, went ahead and had it finished.

I’ll never forget the look on Sanford’s face when he walked in and saw it. He just said, “Hey, look at that.”

Sam, beaming, said, “As LD, I need a place to meet with people, and so there it is.”

Sanford smiled, walked into his own office, and closed the door. He didn’t say a word. But I’m fairly certain he called Charleston before he hit the chair. The countdown had begun again.

The Promotion Ultimatum

Later that evening, while I was alone in the legislative pit wrapping up the day’s work, Sanford walked in.

“Can you keep a secret?” he asked, already committed to telling me regardless of the answer.

“Sam’s done,” he said. “He doesn’t know it yet, but he’s out.”

I wasn’t shocked. I had seen this cycle before. What surprised me was what came next.

I pulled out the stack of resumes and handed them to Sanford. “Here, good luck.”

“I already have the candidate in mind,” he said. “You.”

I just stared at him. This was the same guy who, four months ago, told me I wasn’t cut out for the job. Not organized enough. Too short-sighted. Not ready. And now, suddenly, I was the solution to the problem he created?

I said no.

I told him I had another child on the way. I reminded him, without much subtlety, that he had already said I wasn’t capable. Nothing had changed. There was no new resume. No epiphany. Just an empty office and no one left to fill it.

He kept pushing. I kept resisting. We went back and forth, each volley sharpening the absurdity of the moment. Finally, in classic Sanford fashion, he dropped the hammer.

“Show up tomorrow to be LD,” he said, “or clean out your desk. Just pick one.”

It wasn’t an invitation. It was an ultimatum. And not the elegant kind. It was blunt and transactional. No added pay. No apology. Just a binary choice from a guy who didn’t want to negotiate with the last man standing.

He reminded me, with zero irony, “You just got a raise.”

And that was it. That was the onboarding.

I showed up the next day and started leading the legislative shop. Not because the offer was compelling, but because the work mattered. I believed in what we were trying to do, even if the method of staffing the team resembled a late-night game of chicken more than anything resembling leadership theory.

I didn’t get a ceremony. What I got was a seat at the table, a stack of bills, and the opportunity to build something during Sanford’s final years in the House.

A Strong Finish in the Pit

We had a productive, intense, and surprisingly enjoyable session. We hired smart people. Sanford impulsively hired a couple that I had to let go. We chased down policy wins. We were aggressive.

For a member preparing to leave Congress, Sanford didn’t act like it. We still cared about the fights. We still believed we could shape the debate. And we did.

There were long days and late nights, but there was also a sense of camaraderie. We called it “The Legislative Pit” because our bullpen-style office layout forced everyone to be in close quarters. The proximity meant that debates weren’t theoretical. If you had an idea, you had to say it out loud and defend it. If you disagreed, you didn’t draft a memo; you stood up and made your case. The culture was blunt, but it worked.

Looking back, I realize how much I learned during that stretch. About politics. About people. About pressure. And about myself.

None of it came from being mentored. There was no coaching, no roadmap. The education came from being thrown into the deep end and figuring out how not to drown. There was no choice but to lead, because the alternative was to become the next short-lived LD, replaced before the ink dried on your door sign.

I’m proud of what we accomplished. But I’m even more proud of surviving the system that delivered it.

Same Song, Second Verse

You would think I learned my lesson.

But a decade later, we did the whole routine again. Different office, different title, same tactic. This time, I didn’t even express interest in the job. He just decided I was going to do it. I should have seen it coming because by then, I knew how Sanford worked.

What had changed in those ten years wasn’t the strategy. It was me.

I understood his rhythms. I knew when he was bluffing and when he wasn’t. I knew when he was seeking consensus and when he just wanted a rubber stamp. And he understood that I could challenge him without blowing everything up. There was still tension. There was still friction. But the dynamic was familiar.

The messy part is that it worked. Not in spite of the tension, but because of it.

Ours wasn’t a model of leadership that anyone should write a manual about. In fact, if anyone ever tried, I’d be the first one to warn them off. But it functioned. It produced results. And at its best, it sharpened both of us.

We didn’t always like the process, but we respected what it produced. And sometimes, that’s enough.

What I Learned in the Pit

If you’ve made it this far, you might be asking yourself why any of this matters. It matters because most people only see the polished version of politics: the sound bites, the interviews, and the campaign trail personas.

What they don’t see is how much of it is stitched together with improvisation, ego management, and pure willpower. They don’t see the legislative aides who pull all-nighters to fix a committee draft, or the mid-level staffers who get promoted out of necessity and fear, not because someone had a vision for their potential.

Politics isn’t clean. Movements aren’t neat. Brands are never as bulletproof as their creators believe them to be. What lasts are the stories, the people, and the scars that come with doing real work in a world obsessed with optics.

Would I recommend this model of professional growth? Not unless your HR department has a crisis hotline and a revolving chair budget.

But would I trade those years? Not for anything.

Because while the job wasn’t perfect, the mission was real. The stakes mattered. And I walked away from it not just with scars, but with the skills to lead, to decide, and to take the heat when it came.

And if you’re lucky, maybe one day you’ll look back and realize your greatest political education didn’t come from the job you asked for, but the one you almost walked away from.

Good article! Surprising, but very readable.